When I was about five years old my mother woke me early one morning in May to come outside and see something. Our New Forest pony Jemima had had her first foal, a bright skewbald colt, already up and staggering around on his peg legs. We called him Conker and he soon lost the brown patches and turned snowy white. I can still remember the brightness of the dawn and the thrill of the unexpected: the feeling has stayed with me of good things happening when you are up and about to see them.

My mother was called Hilary Branfoot, was the third of six children, born in 1915; her father had ships in Newcastle and her mother was a doctor. The family lived in a house called Bellshill near Alnwick in Northumberland, pulled down after the war. If you drive up the A1 you can still see the round Bellshill pillars which marked the end of the drive to the house. They had a blessed childhood filled with dogs and ponies, hunting and ice-skating, tennis and endless freedom. There was a butler called Crow and a pony who pulled the lawnmower; it had come out of the coalmines and couldn’t see very well. My mother swapped a tame jackdaw for the first of a long line of Jack Russells, called Crib after the famous boxer.

It all ended when for some unknown reason – why did parents do this? There must have been perfectly good schools in the north – they were sent by train down to school at Sherborne in Dorset. To the end of her life my mother was still haunted with bad dreams about school, struggling with the lessons and being away from home for such long stretches.

Then in the 1930s there was a family misfortune and they moved, bag and baggage, away from Northumberland and into a lovely house called Stonegrave in Yorkshire. When the war came my mother, who had always been practical, kept a few chickens and made some pin money from selling the eggs, joined the Land Army; their brother Tony went off to fight in the desert and two of her sisters became VADs and trained at Catterick. Those two, Dulcie and Joan, were sent off with the vast sum of £10 each and a pep talk ringing in their ears from their father, who warned them to beware of married men with big motorcars and invitations to go out to dinner. Dulcie always used her motorcycle to get around – dressed in a fur-lined flying helmet, heavy hunting mackintosh and an old pair of fishing waders which reached the top of her thighs, with a pyjama cord holding them up and probably a couple of dead rabbits slung on the handlebars so I'd say she was fairly safe from married men in big cars.

Food was uppermost in their minds in war time. If you lived in the country there were eggs and vegetables and butter. At the hospital the shelves were stacked with corned beef and Japanese tinned salmon which some enterprising salesman had relabelled Atlantic Salmon. Patients in the hospital would present with nasty rashes which they insisted was from the Japanese salmon. Dulcie would receive great bundles of Brussels sprouts and hard-boiled duck eggs sent by her mother from home and efficiently delivered by the post office. They did long shifts in the hospital, two weeks on and 48 hours off. She enjoyed it when she was on nights because then there was time to play squash, golf or ride during the day, or skate on the frozen lake at Castle Howard. Lord knows when they ever slept. She remembered one leave in Liverpool where there were hundreds of plump elderly Americans in uniform, jitterbugging, and mussels were always on the menu, cooked every possible way. For the rest of her life whenever Dulcie came across mussels she was wafted nostalgically back to the Adelphi Hotel in wartime.

Warnings of air raids came via the village post office, a few hundred yards from my grandparents’ house in Stonegrave. Granny was the air raid warden as Grandpa was stone deaf. The postmaster had only one leg so when an alert came through he had to strap on his leg, grab his stick and hobble down to blow his whistle under Granny’s bedroom window, by which time the danger had probably passed.

Dulcie remembered spending one autumn leave at home fishing for grayling with Grandpa and going up the church belfry at dusk to catch the pigeons as they came into roost. Nothing was wasted. One day there was a party in the hospital to welcome a handsome new Medical Orderly and the Sisters on her ward were all in a twitter; lipstick was generously applied by all. It turned out that Dulcie had met him before the war and the Sisters and staff nurses seethed when he spent all evening talking to a junior VAD about hunting. Years later she married him.

Meanwhile my mother was happily working on the farm, and took to collecting pig swill at the officers’ mess at Ampleforth (of course she did) which is where she met my father, who was in the 60th Rifles, Kings Royal Rifle Corps. They were married at Stonegrave church in 1942 and my mother wore a dress made by my father’s devoted batman, who was not only an excellent cook and always managed to find my father a bit of bacon in straitened times but also a gifted dressmaker. (I digress but in Sardinia last week when the sewing machine broke we asked a neighbour if he had one we could borrow. Sewing machine? I might be a gay man, he said, but I’m not that gay.)

And so in 1946 when war was over my father came home, my mother sold her little house in Yorkshire and they bought a house in Kent, on the edge of Romney Marsh. It had been thoroughly trashed by the military and needed a lot of work. Before that it had been a home for foundling babies and as a very old man my father often said he heard babies crying in the night. My mother frugally lined her bedroom curtains with old flour sacks and I remember as a child when the early sun shone through you could see the word Prewetts in the lining.

My father went back to the Daily Telegraph and was persuaded to stand for parliament and our mother continued with her smallholding activities, keeping her farm account strictly separate and totting up her income from eggs, honey and lambs and from the Wool Marketing Board. She sold fleeces but also spun wool and was always knitting. My sister told me that our father used to disapprove when she took her knitting to watch the cricket at Canterbury; she did like to keep busy. I was faintly horrified, not long after she died, to discover that Henry, aged five, had dismantled her precious spinning wheel because he had some ambitious requirement for the wheels. Well, she won’t be needing it now will she? he said with a five year old’s logic.

Dulcie and Sandy Blair, her handsome M.O, lived in Helmsley and then when she was widowed she lived right out on the spit in Berwick-upon-Tweed, overlooking the estuary and spotting the poachers stealing salmon from the river. She always had terriers, for some reason always referred to as the little wiggies. She was tiny and stoical and supremely practical. She never owned a washing machine and did all her laundry, including sheets, in the bath. As quite an old lady she was still shooting rabbits from her bedroom window as they browsed on the golf course. And frugal as ever she would put the hot water from her boiled egg pan into a thermos and keep it to make coffee. We used to stay with her for the night on our way up north to go fishing in Invernessshire, Berwick being halfway. I remember a poignant little note by her telephone when she must've been all of 65, saying ‘If I should die suddenly please call these numbers’, with a list of her siblings’ phone numbers. Notwithstanding that she outlived most of them and lived to over100. On the day she died in 2013 I had just been diagnosed with cancer and slipped in the snow and broke my ankle. I've always thought it was Dulcie flying overhead and waving on her way to heaven which distracted me.

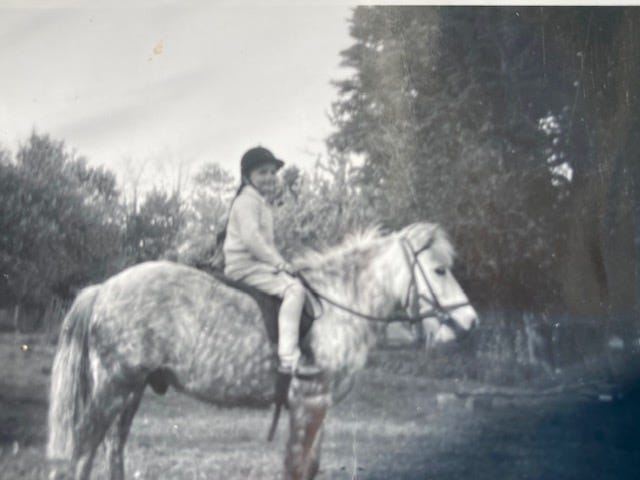

The foal Conker was the sweetest and most patient little colt ever. Aged five I used to run down through the woodland which backed onto our house, climb on the field gate where the ponies grazed and from there onto his back and he never turned a hair. I was the youngest of five and my mother was clearly quite relaxed about health and safety. I don’t ever remember her ever having to officially ‘break in’ any of our ponies; she would lunge and long-rein them and then on one of our brisk walks around the village with her children scuffling unwillingly along and the terriers rootling around in the ditches, one of us would be lifted onto the pony’s back. Conker turned into a brilliant all-round jumping, hunting, pony club, gymkhana pony and we were inseparable for years until I outgrew him.

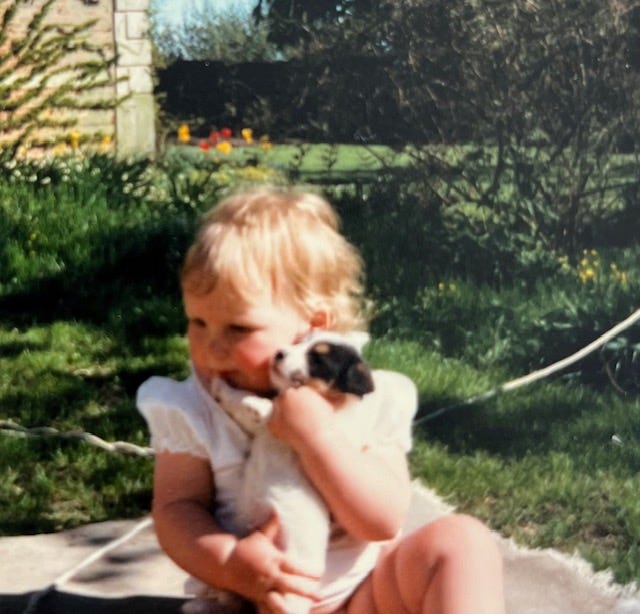

Our childhoods, like our mother’s but so differently from our father’s, were full of cows, sheep and ponies. I used to push puppies and baby goats around in my pram with bonnets on their heads, which they must’ve loved. Every photograph that was ever taken of the family has at least one Jack Russell skulking around in the background. I recently found some pictures of my daughter Sophia, aged about two and clutching some luckless Jack Russell puppy; she now has her first terrier Dennis. And so it goes on.

Such a lovely read thank you xx

What a different world our parents and grandparents lived in—how shocked they’d be to see how pampered we are today!